Why Invest in First Time VC Managers?

Every successful VC manager was a first time manager once. In fact, they may have been more successful when they were first-time than they are expected to be in the future. In this blog post we’ll give a few reasons why that may be and why first time managers should have a place in a well diversified portfolio of funds and why they deliver an appropriate risk adjusted return just like seed stage startups do.

“BEYOND THE LONG TERM”

Andy Golden, the President of Princeton University Investment Company (PRINCO), states as one of his key investment principles “Look beyond long term”. What does that mean for him? According to Marcelino Pantoja of Capital Allocators, it means searching for new fund managers and committing to them before other institutional investors discover them.

Princeton picks perhaps three new investment firms a year. By design, two-thirds have less than a three-year record. Golden can build a meaningful position in the most successful companies by getting in early. Once an investment company becomes successful and well-known, everyone wants a piece, and entree becomes tougher. That strategy has led to some of his biggest successes, such as buying into Horowitz’s VC firm, Andreessen Horowitz LLC, before it struck gold with investments in Facebook and Pinterest Inc. Others seeking to capitalize on that success later had much harder time to get access - the best VC funds are oversubscribed and do not accept new investors, as their target investment markets are of limited size. There is a similar example from Europe: Skype, which is still Mangrove’s best investment in terms of returns, was also their very first one ever.

Entrusting money to untried companies requires using a mix of intuition and character judgment - similar to investing in seed stage startups, where founders are usually the only thing to go by. Without intervention, the selection process tends to favor companies whose owners are already part of Princeton’s network and can therefore seem familiar, an implicit bias that can work against women and minorities—something Golden is seeking to counter, however slowly.

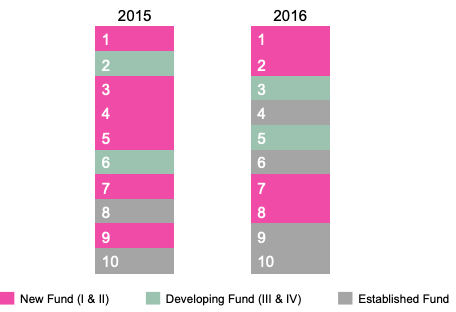

He is optimizing for discomfort by hiring skilled investors with limited experience in managing a fund. The goal is that they will invest in overlooked opportunities and return capital many times over. The outsized return expectations do seem to pay off: in 2015 and 2016 (the latest years for which data is available), according to Cambridge Associates, a first or second time fund was at the top of the US Top 10 VC funds by TVPI:

The same is true in Europe: even though first time and emerging fund managers are not defined exactly the same, out of European Investment Fund’ top five funds, four were emerging managers.

REASONS BEHIND THE SUCCESS

Reasons behind first time manager’s success predominantly have to do with what makes the entire asset class so attractive to investors - alignment of interests. But in the case of the first time managers, that alignment is even more extreme and extends beyond the limited partners to portfolio companies as well. As first time funds are by definition managed by the people who built the management firm, they are founders themselves and much better able to empathize with portfolio company founders than the junior employees that many mature firms hire to outsource the investment sourcing work to. As a result, the first time fund managers are able to find more capable portfolio company founders and build better portfolios.

First time managers are hungry for success and recognition. And they get to keep all of the incentivisation from the performance fees. Whereas in more mature managers, where the team has gone through many changes and the original partners have gotten tired and taken a step back, the incentives are often misaligned as a lot of the incentivisation flows to people not actually actively sourcing deals or making investment decisions, just because they were there in the beginning, “built the brand” and hold the fundraising relationships with the Limited Partners. In addition to performance fee misalignment, over time management fee misalignment builds up as well - bigger and bigger funds raised mean bigger and bigger fees but not necessarily quality purposes to spend them on - the marginal return on new hires diminishes eventually and also nowadays technology and automation do what armies of juniors used to have to do on deal sourcing and screening. Small teams of a few partners with good and cheap technology at their fingertips can achieve nimbler and faster decision-making than bloated teams, therefore guaranteeing access to hotter fast-moving transactions. When VC managers start to take dividends from management fees, which generally happens around the fourth fund, it can be assumed that the hunger of the early days is no longer there.

DIVERSE PERSPECTIVES OF TOMORROW

Many mature managers are caught in the golden handcuffs of their track record - what they successfully did in the past may not work again in the future as the markets have moved on, but they still have to present that as a viable strategy, as it is so much easier to raise funds promising to invest in exactly the same things that worked in the past.

Emerging VC fund managers hold the investment perspectives of tomorrow. Because an increasing number of emerging managers hail from diverse backgrounds, they have access to untapped sources of deal flow, focus on different geographies and verticals, and use new investment models. For example, women led VCs are two times more likely to invest in woman-led startups. Furthermore, the Harvard Business Review found that VC firms with more female partners (10% more) had 1.5% higher fund returns, and 9.7% more profitable exits. . In order to get access to certain diverse kinds of thinking, investing in a first time manager may be the only option, as certain groups of people, among whom talent is distributed as equally as elsewhere, have simply not previously been allowed to manage money, family-owned or otherwise, and may therefore not had equal opportunities to create track record.

We’ll write a separate post on benefits of diverse managers, but here’s a short warning to not assume that someone’s dealflow networks are worth less just because they don’t look like the dealflow networks of those who have traditionally occupied this industry

HOW TO OVERCOME OBSTACLES TO INVESTING IN FIRST TIME MANAGERS?

Many first time funds are too small for allocation. That’s ok. You can commit to multiple generations. Or you can commit to a group of them at once and put an SPV in the middle so it still looks like just a single line in your portfolio if that’s what you need.

It’s easier to re-up. You feel like there’s an established relationship of trust. True, but that also may lull you into a false sense of security and may end up costing you in returns. You want the manager to want to earn your trust. They will work twice as hard for that if they feel they need to earn it, they will be hungry to establish themselves in the market and will be grateful for the opportunity, be it through sharing co-investment opportunities or making introductions to strategically interesting portfolio companies.

PITFALLS TO AVOID

Do not approach a first time manager like you would approach a mature manager. The first time manager will always lose out if you use the same criteria. But using the same criteria is erroneous - you wouldn’t use the same criteria to evaluate a pre-revenue startup founded two years ago and a $100m annual revenue run rate unicorn, even though both of them may still be burning bottom line cash. And moreover: the criteria you use to evaluate the mature manager may be so backward-looking as to miss out on important fundamental shifts underway for the future.

WHAT DO FIRST TIME MANAGERS NEED?

The main issue is that most Limited Partners are not aware of the above statistics and rationale. So what first time managers need is for the word to spread about this.

Write first comment